I AM AN INDIGENOUS ZAPOTEC ARTIST, CURATOR, EDUCATOR, AND COMMUNITY ACTIVATOR BORN AND RAISED ON QUINNIPIAC LAND. LAND THAT IS NOW KNOWN AS NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT.

I BELIEVE THAT ART IS FOR EVERYONE.

I BELIEVE PEOPLE, NOT INSTITUTIONS, GIFT US REAL CHANGE.

I BELIEVE COMMUNITY TAKES CARE OF ONE ANOTHER.

AND I BELIEVE ONE OF THE GREATEST INVESTMENTS WE CAN MAKE IN OUR OWN COMMUNITIES IS TO YOUNG PEOPLE, THROUGH MENTORSHIP AND EDUCATION.

MORE ABOUT ME HERE

SCROLL DOWN ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

I BELIEVE THAT ART IS FOR EVERYONE.

I BELIEVE PEOPLE, NOT INSTITUTIONS, GIFT US REAL CHANGE.

I BELIEVE COMMUNITY TAKES CARE OF ONE ANOTHER.

AND I BELIEVE ONE OF THE GREATEST INVESTMENTS WE CAN MAKE IN OUR OWN COMMUNITIES IS TO YOUNG PEOPLE, THROUGH MENTORSHIP AND EDUCATION.

MORE ABOUT ME HERE

SCROLL DOWN ︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

TO VIEW WORK

WORK (CLICK TO VIEW)

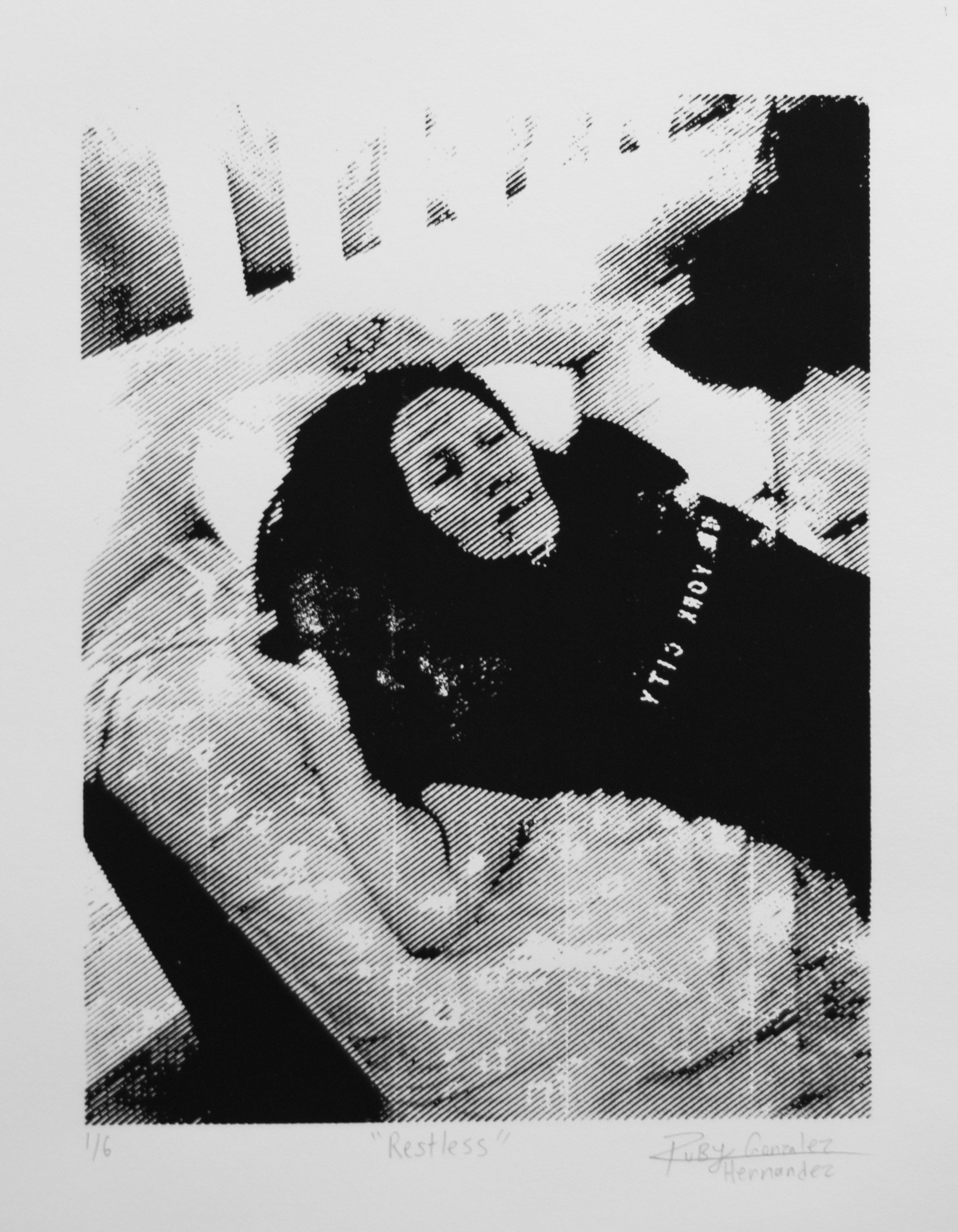

amor eterno

(ETERNAL LOVE)amor eterno is about the daughter. the identities of being mexican, Indigenous, latinx, and first gen seep in and through. the love that machismo doesn’t give her. the love she cultivates, that learns to grow through stone.

cell phone images turned seriagraphs(silkscreen)

ink on paper

dimentions variable

2019

WORK (CLICK TO VIEW)

SCROLL TO VIEW WORK AND INTERVIEW ︎︎︎

SCROLL TO VIEW WORK AND INTERVIEW ︎︎︎

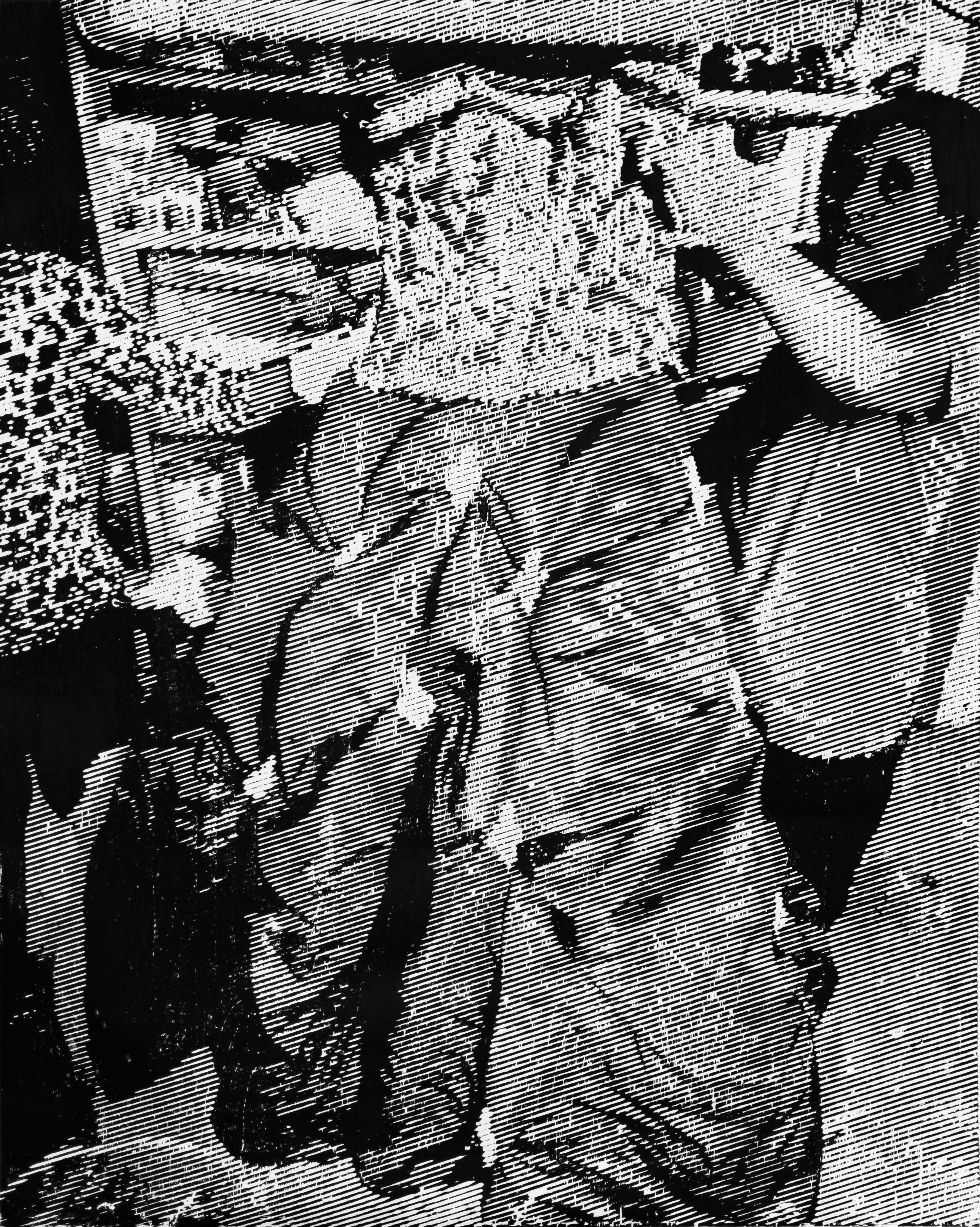

SUBSEVEN

2021-now

meaning???

~ A computer virus that takes control, trojan horse style

~ A midwest Christian rock band (disbanded, but gave 14 yr old me inspo)

~ (Sub)mission unto God(7)

I made this work to speak to someone I once was, in a language only she understood. From 6 to 16 years old, I was raised in a very controlled, strict religious Pentecostal upbringing. It was what I would later learn to be a cult. I was taught that the world only existed in black and white, as either right or wrong. There was only one way to earn love and salvation from God, and that was through following a strict set of rules and harmful mindsets, without admitting it outright. I am speaking to my fourteen year old self in Freedom Had A Bitter Taste, articulating the illusion that freedom was implanted as; a dead end, as well as the reality of life on the other side of those stone walls. It is definitely a recollection. This “outside world” was described as this God-forsaken, desolate, spiritually empty wilderness. I knew what true freedom meant, but I was so engulfed in the flame of radicalism that it took time to feel in my chest. Subseven shows a peek into what that was like as well. I knew that the ideas I was fed from a young age were wrong, but this was the only map I had to view and navigate the world when I held my own autonomy in my hands for the first time. This work is an acknowledgment to a 16 year old self that made a decision to leave at her sweet sixteen celebration. Through her, God gave me the life I have now.

As a photographer, I found myself drawn to use my cell phone to make this body of work. This series, SubSeven, meaning submitted to God, includes photo woodcut prints on paper, as well as digital photographs. I made the majority of these photos in East Rock park in New Haven, and deconstructed them to turn into woodcuts. Using software, I turned them into computer commands, also known as G-code, to run through and become engraved onto wood using a CNC machine (or a computer numerical controlled machine). The final step is the traditional printmaking method, using this engraved wood to print them onto paper like a stamp.

Freedom Had A Bitter Taste

Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez with Danni Shen

(This interview is taken from the Yale Doran Artist-in-residence Cataloge, view it in full here)

This interview takes place after an initial conversation with the artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez (b. 1998, New Haven) about her current body of work in-progress as a 2021–2022 Yale University Art Gallery and Artspace New Haven Happy and Bob Doran Artist-in-Residence, “Subseven,” which is a series of large-scale, black and white, digitally-engraved, woodcut prints that serve as self-portraits and portals into simultaneously destructive and transformative moments in the artist’s life. The obliteration of a series of original images becomes a central methodology by which she represents past and present versions of herself. The mirror embedded in the natural landscape—for example, atop the winding trunk of a tree—is also a recurring motif that at once reflects and fragments different parts of the body that then seem to re-emerge from this journey through the wilderness, though it is one that isn’t too far from home. In her process, Gonzalez Hernandez takes digital photographs near her home in New Haven, Connecticut in sites of personal and spiritual significance. After further digital deconstruction of these images into linework, the artist translates them into code that is engraved by a CNC router. Following these multiple layers of manipulation, the machine, via a programmed bit extension, engraves large panels (a 48 x 36 in. work requires up to eleven hours per panel) of wood from which the artist then creates the final woodcut prints.

The following interview delves further into her personal and family religious life. These histories have deeply informed her practice, which navigates cult collectivity and individual choice, obsession and happiness, as well as beliefs around autonomy, identity, God, perfection, trauma, vulnerability, and freedom that coalesce in this new series.

Danni Shen (DS): You mention that the piece entitled Mi Hermosa Princesa II (My Pretty Princess II) in particular for you is also representative of a kind of door or threshold in your life. This photograph of your mother (right) and great aunt (left) holding up your dress from your sweet sixteen celebration, documents a pivotal day in terms of a decision you made for yourself as well as relationships with your family. Would you be able to elaborate on this image and its personal history in relation to your work here?

Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez (RGH): This cell phone photo turned woodcut is the first in this series. I call this image the door to “Subseven,” because I wore this dress to my sweet sixteenth birthday party to mark the decision to leave Pentecostalism. This faith is an evangelical Christian religion, whose rules vary slightly by church, but often can include forbidding alcohol/tobacco, any kind of dancing, and most all music, radio, and television in order to gain favor with God. Additionally, for women, this often includes the forbidding of makeup, cutting hair, leadership positions, and immodest dress (wearing pants). At sixteen, I had dedicated ten years as a member of the church with my family, and we (being my mother, brother, and previously, father) held pretty high positions within that community. As much as I wanted to leave quietly, it wasn’t going to happen. When I began creating these photographs, years after my departure from this faith, it solidified that though I was undoubtedly relying on intuition, inexplicable at times, I was yearning to speak to someone I once was. In a way, trying to work through finding answers to questions I hadn’t completely understood yet.

DS: After leaving behind your past circumstances where asking questions was prohibited and your identity was preconstructed and given, you said you were left with a sense of freedom, but one that felt bitter. When the opportunity came to decide your own beliefs, you mentioned there came a realization that what had been presented to you as beautiful and docile, was actually violent and destructive in the light of your newfound autonomy. This feeling/memory is also encompassed in the piece entitled Freedom Had a Bitter Taste, which depicts what looks to be a small enclosure or dead-end surrounded by brick walls and backgrounded by forest. Could you speak to how your relationship to “freedom” has changed since that time and how making art might be a kind of recollection/catharsis of the past, but also a transformation of the present into the future?

RGH: Yes! Holding my own autonomy in my hands, absolutely was the end of an entire life I lived. This realization of destruction sprouted years before I left the church, and slowly built into a full understanding. I knew what true freedom meant in my mind, but I was so engulfed in the flame of pentecostalism it took time to feel in my chest. Following this intuition, leaving was still bewildering. To put it in perspective, I had to learn how to feel comfortable wearing a t-shirt in public. So, I am speaking to my fourteen-year-old self in Freedom Had A Bitter Taste, articulating the illusion that freedom was implanted as; a dead end, as well as the reality of life on the other side of those stone walls. It is definitely a recollection, viewers are both looking at this past self in that mirror, and viewing the present and future as this past self looking in the mirror, in the way they understand. I’m definitely referencing the past, because this is what the world looked like when I left the church eight years ago. This “outside world” was described as this God-forsaken, desolate, spiritually-empty wilderness. Originally, these images created at East Rock last summer look SO lush, and green, but I chose to translate them into these black and white deteriorating lines because I’m speaking to someone I once was, in the language she understood. This visual language that needed to exist equally needed to be brought through the method of working, and follows the same painful dialog to physically imitate what it took to get here: cell phone image programmed and translated a few ways into what eventually ends up becoming G-Code computer commands, engraved on wood via a CNC router, and imprinted on paper.

DS: Can you tell me more about the overarching title of this series “Subseven”?

RGH: Oh gosh! Yes, Subseven means submitted to God; and, in making this work, I chose this title to center the idea I used to leave the church, to submit literally to God and and use their interpretation of biblical truths against them. I literally used their own words against them, because they were not following them. This work is not about the cult I grew up in, but the acknowledgement of a small choice from someone I once was, to become who I am now. I am eternally grateful that I submitted to God.

DS: In your bio you identify as an Indigenous Zapotec artist who creates visual language for “religious exploitation, spiritual salvation, redemption, oppression affecting BIPOC, and more.” I’d love to hear more about your current ideas around your own identity/positionality and relationship to collectivity.

RGH: My identity surprisingly enough is still very much found in Christ, this time constructed differently. I inspect each and every thread of my life to ensure it’s mine, and it feels beautiful. Accessibility has become an important value in my life. Much of what I create visual language for comes from not always having the ability to speak accurately on the weight and depth of the subject—on the spot. What’s given me the opportunity to leave a church, is now an avenue I invest in. In relation to collectivity, I am still very vigilant about what I invest my time in. It is very easy for people who have this similar experience to fall back into an obsession of some sort. Keeping this in mind, there is a beauty I have been waiting for all of my life in the community I have now. It is very important to me that I have the support of my community, and that I can in turn also provide support. My family and New Haven gives me so much joy. And I have chosen to spend my artistic practice investing back into soil that’s granted me the respect and dignity to grow.

DS: You are not only an artist but also a curator and connector. How do these multiple roles inform your work/approach or how you hope to continue working on upcoming/future projects?

RGH: In everything that I do, across my artistic and curatorial practices, the center of it is for people, regardless of their education or experience engaging with art, to have the ability to enjoy and digest art without feeling like it’s too far away and exclusive to understand. I’m not interested in anything that isn’t aligned with this vision. I used to think there wasn’t an argument to be had, that this wall the art world tends to build could be attempted to be broken down. I was systematically pushed out of university, and just figured it was my own problem to fill in the gaps to get to the unreachable. And then I started really meeting the community here in New Haven—artists, art-lovers, activists, organizers, educators, students, connectors, and the list goes on—and I was thrilled to change my mind. I never expected to come across hundreds of New Haveners that held an inclined ear towards accessibility in the arts. I’ve learned so much from New Haven by listening, and I am going to continue to invest back in. I plan to expand an annual international print exchange I run called Lunch Money Print. It exists as a platform to provide well-made and thought-provoking contemporary art that is affordable to everyday people, while also supporting the artists who create it. Artists submit an edition of 11 prints, 10 get traded with participating artists from around the world, and the 11th print gets put up for sale. All profits made from sales go back to the artist. I’m expanding this by planning to host community-centered exhibitions, commissioning artists to create installations alongside this work.

Instagram, Twitter

Digital Photography

DARKROOM PHOTOGRAPHY

SILVER GELATIN PRINT